Bright Futures in Healthcare

Clark’s Allied Health programs honored this year’s graduates with two noteworthy ceremonies, celebrating the achievements of our nursing and dental hygienist programs.

Dental Hygienists Stand Proud in Purple

Graduates and families were dressed to the nines at this year’s Dental Hygiene Senior Recognition. It was an elegant affair, with purple balloons and flowers – the program’s signature color – adding to the celebratory experience.

Students and faculty had a lot to celebrate. This year’s dental hygienist students examined 651 patients, completed 76 weeks of school, and passed 64 exams – a testimony to the time and effort they put into building their futures. As Danielle Hovey, this year’s student speaker put it, “You can’t spell HARD without an RDH.”

But the hard work paid off. Throughout the evening, students were honored with awards, accolades, and heartfelt gratitude for their dedication to their education.

“You remind people that they matter,” Professor Kristi Taylor said in her welcome toast. “Just by showing up and doing what you do best.”

Clark Vice President of Instruction, Dr. William ‘Terry’ Brown spoke to the graduating class, sharing a story about his first time at the clinic, when student Liliya Dudko pointed out something on his x-ray that no dentist of his had ever caught before and then encouraged him to practice proper dental care.

“That is the care and passion that clinicians ought to have for their patients,” said Dr. Brown.

In addition to honoring the graduates, the evening recognized the newest inductees of Sigma Phi Alpha National Dental Hygiene Honor Society: Zoe Demming, Courtney Smoke, and Kayley Ward. Additionally, students were presented with numerous awards that showcased the dedication of the graduating class. Congratulations to:

- Kayley Ward, The Western Society of Periodontology Student Award

- Leisa Perrin, The Colgate STAR Award

- Amber Nicotra, The Student-Voted Pure Award

- Allana Guild, The Golden Scaler Award

At the conclusion of the event, students also presented awards to the instructors. Each instructor was given a plaque engraved with a saying or lesson that they had shared with the class this year. It was the perfect way to highlight the relationships that were formed among students and faculty throughout the year.

About Clark’s Dental Hygiene Program

The Dental Hygiene program provides classroom and clinical experiences that successfully prepare students for the national board exam and various clinical licensing exams. Students serve the community by participating in oral health programs in area schools and caring for patients at the Free Clinic of Southwest Washington and other local facilities serving the community. Upon completion of the program, students earn a Bachelor of Applied Science in Dental Hygiene Degree.

A Milestone moment for Nursing Program

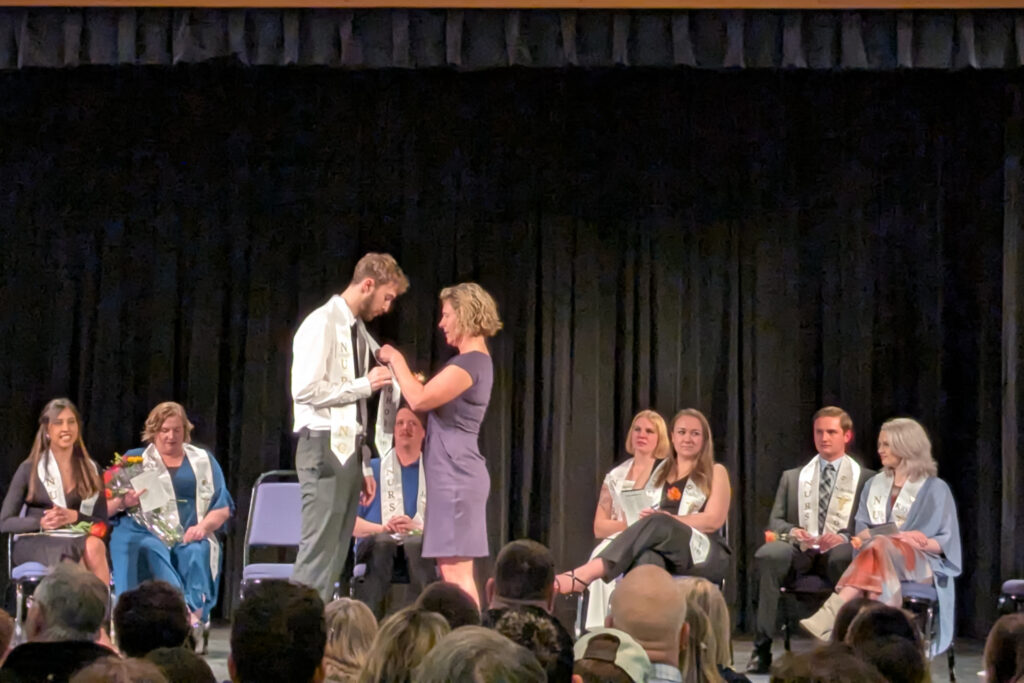

Clark College recently celebrated a historic achievement—its 150th nursing cohort—with a heartfelt pinning ceremony honoring 24 graduates. More than just a tradition, the event marked the culmination of rigorous training and the beginning of a new chapter in healthcare. Each graduate was joined on stage by a chosen supporter—whether a parent, partner, or close friend—who placed the nursing pin as a personal message was read aloud. A slideshow of photos and quotes added to this tribute.

Graduate Keaton Wilbanks spoke on behalf of the class, highlighting the clinical and academic experiences shared by the cohort. “We shared many firsts—first codes, first live births, first times facing death, our first experience with postpartum care, and having discussions with patients about conditions that will kill them,” Wilbanks said. “We showed up, we stayed, we supported each other. Somewhere along the way, we stopped being students in competition and became nurses as part of a much bigger community.” Wilbanks post-graduation plans include traveling the country with his wife, and work in critical care before applying to CRNA school with plans to be an anesthetist.

The ceremony included remarks from Clark College President Dr. Karin Edwards, Vice President of Instruction Dr. William “Terry” Brown, and Associate Dean of Nursing Jennifer Obbard. Professor Gabriele Canazzi provided a history of the nursing pin, and Professor Halina Brant-Zawadzki brought the graduates roses and read The Rose That Grew from Concrete by Tupac Shakur.

Jenny Fredrickson presented Emily Johnson with the Clinical Excellence Award. The award is based on professionalism, communication, clinical preparation, use of the nursing process, and organization. Johnson passed her NCLEX-RN exam and has been accepted to a residency position in critical care at Legacy Salmon Creek Hospital. She will also be starting the BSN program at Washington State University in the fall. The ceremony concluded with the nursing pledge, led by Angie Bailey and Mckenzie Montalvo.

History of the Nursing Program at Clark College

Clark College’s nursing program began during World War II, offering Nurse’s Aide training in response to labor shortages. In 1964, the college graduated its first class of 15 nurses from a newly developed associate degree program. Jean Hamilton, the program’s first director, helped establish the program—the first of its kind in the Pacific Northwest and the fifth in the country. She designed the curriculum to be transferable, enabling graduates to pursue higher degrees.

Prior to that, most nursing education occurred in hospital-based programs. When St. Joseph’s Hospital closed its nursing school in the mid-1950s, Clark College began offering practical nursing courses to meet regional demand. The program has continued to evolve, preparing nurses for entry into the profession and further academic study.